Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

If you are a student or a guest researcher (like me) in Berlin and you need to get or renew a visa or need to change your visa status, you need to wait. The Ausländerbehörde (Immigration Office), which serves Berlin’s non-German citizens, is open three days a week (Monday and Tuesday from 7am to 2pm, Thursday from 10am to 6pm) and as a student you cannot make an appointment. Instead, you have to arrive during office hours and take a number. If there are no more numbers, you cannot talk to an official and you have to try again. Usually you learn, through trial and error, that you must arrive at least one hour, often two, before the office opens and wait outside in order to get a number. It is always nice when your visa renewal time falls in the summer rather than the winter months.

There are no instructions on the official website to tell you about these lengthy waiting times (not even in German!), and no officials offering information about the procedure. The small amount of information you can gather about where to stand and how long to wait comes from the people around you. Everyone waiting uses the language resources they have: L2 German, English, Turkish, among many other languages, attempting to work out if the person ahead or behind them has better information about what is going on. During the wait, strangers share stories about previous experiences at the office.

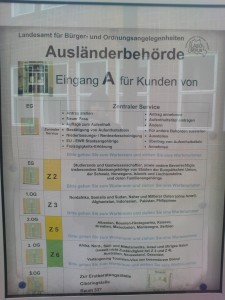

The monolingual German signage at the Ausländerbehörde stands in stark contrast to the linguistically diverse waiting crowd.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Berlin, in general, is a multilingual city. You hear many languages as you walk the streets: you learn Turkish words when you do your groceries and read ads in Polish, English and Arabic, alongside German, on the trains. The government department for Integration and Migration makes their website available in German, English, Spanish, French, Polish, Russian, and Turkish and boasts that Berlin “was and is a city of immigrants. Immigrants from numerous countries”. 13.7% of Berlin’s population are not German citizens. Why is it then that at the Ausländerbehörde, where clients by definition speak German as an additional language if at all, there is no multilingual information?

Not only is the limited official information provided only in German, it is contradictory and confusing. The writing is small and it takes a number of readings to work out which floor it is you need to go to. In fact, on my first visit I read the sign (above), saw ‘Australien’ and, after confirming with the woman at the front desk (who told me she does not have a phone line, so cannot call any of the offices to get further information), I went to wait on the 3rd floor. After finally talking to an official I was sent to the 1st floor where I was meant to be waiting (as a guest academic) to wait some more.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

There are a few glimpses of recognition that people navigating the immigration office might need assistance beyond this monolingual signage. A smaller sign (left) indicates the separate entrance for Turkish nationals, the largest group of applicants in Berlin, and includes the German for the country’s name in addition to the Turkish flag. It is unclear, however, which entrance you should choose if you are a visiting academic from Turkey. There is no Turkish language presence at all, only the Turkish flag acknowledging Turkish nationals while quietly insisting on German monolingualism.

What does all of this say about language on the move and social inclusion in a multilingual city? The Ausländerbehörde makes it clear that the nation remains the great arbiter of access to resources and that exclusion is enforced through lack of information in even the major L2s of the country. Offering information in other languages for ‘Ausländer’ (foreigners) challenges the legitimacy of the one language, one nation tie and yet for the people waiting in line speaking, multilingualism is the only way to access information.